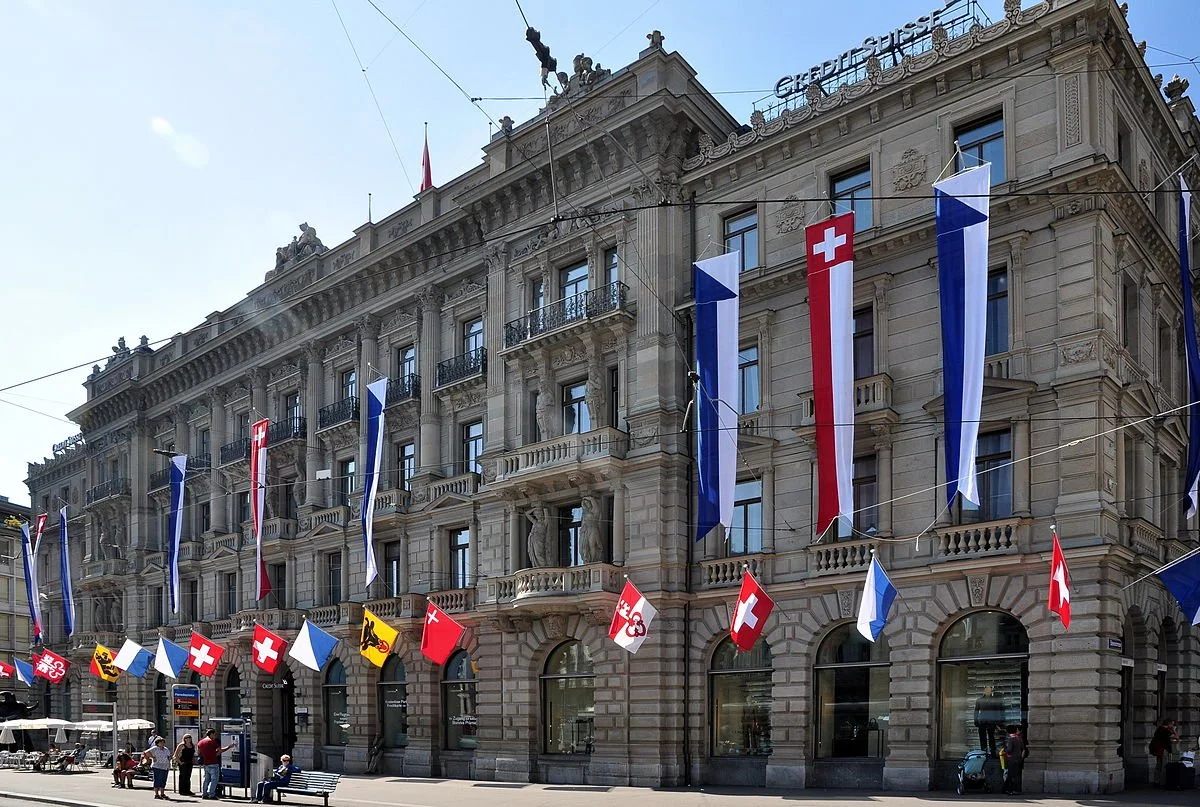

Suisse Secrets: Credit Suisse's dubious client list opened for scrutiny

Photo: Roland zh. CC BY-SA 3.0

A major leak of account data from Credit Suisse demonstrates systematic compliance failures at Switzerland's second largest bank. Information about 18,000 accounts held by non-Swiss nationals shows that criminals, individuals under international sanctions, political actors from fragile or authoritarian states and intelligence officers were among Credit Suisse's customers.

The data reveals just a fraction of Credit Suisse's business. The company has over 1.5 million clients and employs nearly 50,000 people. Much of Credit Suisse's activities are protected behind Switzerland's tough banking secrecy laws, which make it an offence for journalists to possess banking data, even if they do not go on to publish it.

According to the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), those given banking services by Credit Suisse included "the family of an Egyptian intelligence chief who oversaw torture of terrorism suspects for the CIA; an Italian accused of laundering criminal funds for the infamous ‘Ndrangheta criminal group; a German executive who bribed Nigerian officials for telecoms contracts; and Jordan’s King Abdullah II, who held a single account worth 230 million Swiss francs ($223 million) at its peak, even as his country raked in billions in foreign aid."

Compliance experts cited by the organisation noted that these figures' history was public and well known and that other institutions would likely not have accepted them as customers.

In its response to the leaks, Credit Suisse claimed that the data was "predominantly historical" and the "overwhelming majority" of accounts cited by media as problematic had either been closed or were in the process of being so.

Former Credit Suisse employees described a corporate culture that incentivised executives to open lucrative private accounts, even where there was a known reputational risk. Compliance became less rigorous over a certain financial threshold and operated under a rule of "plausible deniability," where it was expected that potentially difficult questions would not be asked by others within the organisation. The holders of some accounts might be be known only to certain senior executives.

48 media organisations participated in the Suisse Secrets reporting consortium, organised by OCCRP and the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung. There was no Swiss media partner, due to the potential legal risk of working with this information within Swiss borders. OCCRP found that former and current Credit Suisse employees were reluctant to corroborate their findings on the record due to the bank's history of pursuing former employees through the court.

Switzerland's culture of banking secrecy has come under increased pressure in recent years. Since 2018, Switzerland shares US and European customers' tax information with their countries of nationality under the Common Reporting Standard (CRS). As critics have pointed out, however, this reporting system excludes countries where governance is weakest and the risk of corruption, tax evasion and resourse extraction is most acute.

In the wake of the Suisse Secrets leak, a majority of MEPs have called on the European Commission to consider whether Switzerland should be added to a money laundering blacklist.

Credit Suisse itself is currently being pursued through the Swiss courts for allegedly allowing a group of Bulgarian cocaine dealers to launder millions through the bank's accounts, despite warnings, media reports of criminality and suspicious deposits of suitcases full of cash.